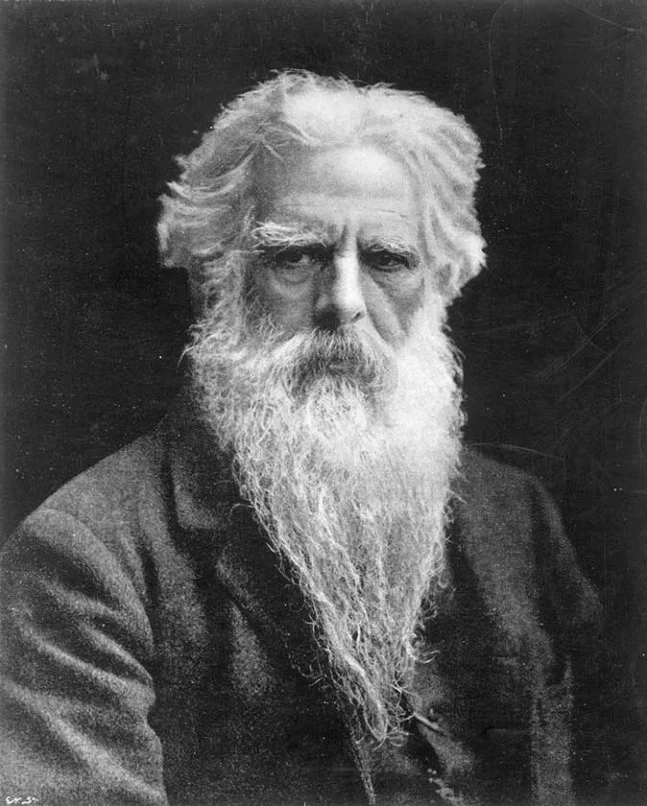

Eadweard Muybridge was the first artist of film. Everything before him (and rather a lot since) was just technical demonstration, but Muybridge in the 1880s was doing more than that. Chickens Scared by Torpedo is a locomotion study featuring some chickens reacting to several small explosions from torpedoes, and it’s a somehow captivating image. More than just a demonstration of motion, this film lets us reach into the mind of a man 140 years ago. The choice of subject is so unusual that it demands historical or psychological explanation, and the dynamic activity is interesting in and of itself, not simply as a vehicle for the technological demonstration of the camera. Why were Muybridge, some chickens, and some torpedoes all in the same place, and how was he in the position to cause these explosions for his study? Even now that the internet has made zero marginal cost for video distribution possible it’s still unusual to see people who have the means to make something like this, so what circumstances could have allowed this one? It’s surely not an astonishing story, but it’s one that tugs at the corners of my mind while I watch the choppy footage.

As a cat lover I was delighted to find that Muybridge had produced this film of a cat in motion, since the more famous galloping horse has never done much for me. But this film is in fact qualitatively different to the study of the galloping horse beyond simply featuring a subject I am more personally fond of. The collection of images, apparently never intended to be assembled into a film strip and projected, is concerned not just with the motion of the cat’s run, but with the process of change between the trot and run. Though it still succeeds as a document of the cat’s motion, its interest in transition makes it a properly cinematic experience. Apparently satisfied with an exploration of speed, now velocity is explored and what is revealed is a lopsided muscular shifting and a graceful bounce—at once beautiful and awkward, in that way that biological processes often are.

But, look at the way the image melts into the background! Sections of light and shade on the cat’s body are rendered such that the image becomes not some record of the natural proliferation of light, but as a contour of near and far. Form, represented only in black ink, is distinguished from the surrounding formlessness only by the empty space of the rough canvas.

This Song dynasty painting by an anonymous painter portrays its animals in exactly the same way. The rich colours of the landscape dominate, and the deer, though centrally placed and eponymous, feel translucent in their representation as subtle contours rising up from the flat brown silk. The properly ancient brown silk of the song dynasty complements its subjects, and Muybridge's cat bubbles up out of a grey, almost grubby canvas. As with all early works in a developing medium Muybridge's work feels ancient, though it isn't really so when compared to the Song dynasty paintings. The earliest rock and roll recordings feel similar ancient, though they first appeared a lifetime on from these locomotion studies. This curiosity of a relative antiquity is actually materialised in the film: the grubby canvas material feels ordinary and contemporary, and yet it supports the impression of this cat. In human years this cat is at least 135. In cat years, a seventh as long, this would make him 945. Roughly a contemporary of Herd of Deer in a Maple Grove. As an ancient creature appears to emerge from the still surface of a flatly modern pool, it overwhelmingly translates the dialectic of near and far into a dialectic of new and old, and of material and spirit.

Zdzisław Beksiński, the Polish painter known for his fusion of pulp fantasy horror and delicate surrealism, developed such a dialectic himself in his later works. What was once for him a technical problem of accurately rendering figures and buildings emerging from mist—a problem of representation—became a dialectic between representation and abstraction.

What were once self contained worlds, internally consistent and rendered such that they might be real if only for a suspension of disbelief, began to be self conscious art pieces where any ostensible representative element in the piece emerges out of an abstract surrounding flatness.

Beksiński is well known for painting in his waking hours what he would see in his nightmares, but while this may be true it suggests a narrative about the work that I think he himself would not have liked. He was apparently a very funny man, even silly and playful. More insidious than a reductive emotional narrative around his work is the persistent Anti-Communist streak in the Western European and American interpretations of his art: Beksiński purportedly was so disturbed by the rapidly improving material condition of the working class in Poland that he was driven to criticise the totalitarian government by painting spooky images.

I wondered if there was any information on the situation with the Muybridge and the chickens and torpedoes, and found nothing about that online. What I did find, however, is Muybridge was born ‘Edward James Muggeridge’, but changed his name several times to make it more in line with the archaic Anglo Saxon spelling. In 1860 he suffered a debilitating head injury in a stage coach crash after which he was erratic and prone to outbursts of emotion. In 1875 he murdered his wife’s lover, and then while in prison passionately defended a fellow Chinese inmate from racist abuse on the grounds that "no man of any country whose misfortunes shall bring him here shall be abused in my presence". I wonder, if I were the sort of person who might make crass, reductive generalisations about Beksiński and his art based on what I learned in 10 minutes of reading about his life, what would I do with this information about Muybridge? No obvious narrative emerges—no easy route to interpretation. Even obvious aesthetic choices cannot be mapped onto some standard of value by the artist. Muybridge—the Anglo-Saxon enthusiast, passionately anti-racist, cold blooded murderer with brain damage—made dramatic, dynamic, technologically avant-garde art featuring animals. Looking attentively at that art, as with any other art, or social convention, or anything at all, is a catalyst for the furious building of mental connections and realisations if one is inclined to let that happen.

When Did Photography Become an Art?

Irving Penn and Vitalina Varela: Variations on Tight Spaces

Decorating Space and Time