Some months ago, during the winter of the second British lockdown, I decided at some point to take a walk in a straight line in some direction as far as I could before turning back. The mechanism of practical necessity often informs—or indeed totally determines—the routes we walk. The pandemic throws an easy example of this in that, as a key worker living in lockdown, I would move in straight lines, back and forth, between my house and the shop I work at every day in and make no other journeys. Pre-pandemic walking was more open ended but tended still to be governed, more or less, by practical considerations like having to go to various shops or bus stops or friend’s homes. We don’t walk like bluebottles fly: there is not enough arbitrary motion for my liking in the paths taken by the modern walker. So: I walked in a straight line in a pretty much random direction. I kept doggedly to this line, as far as the winding streets would allow, and after about an hour of walking I discovered a beautiful old church which I would not have found otherwise. I carried on going for many more hours until the nightfall convinced me to turn back.

I have made the beginning of the same walk many times since, but have never gone past the church again. The walks used to be irregular, according to my random whims, but after one stop in the churchyard I started trying to arrive at the same time every week. On the occasion which was to end my improvisatory return to this place, and establish a regular routine of return instead, I had brought some books to read in the deserted church yard. The yard is smallish, compared with what one might expect for the size of the church anyway. There are three benches: one of them is too close to the road and another is right outside the main gate of the church, which makes me feel like I’m sitting in a waiting area before being allowed to go in. I use the third bench, which is around to the side. If I had used another bench that day, I might have sat and read for a while before becoming dimly aware of the barely perceptible drifting of music. The bench I did sit on, though, is right next to a small side door with a very wide keyhole, and so I heard the music coming from inside the church before I even sat down.

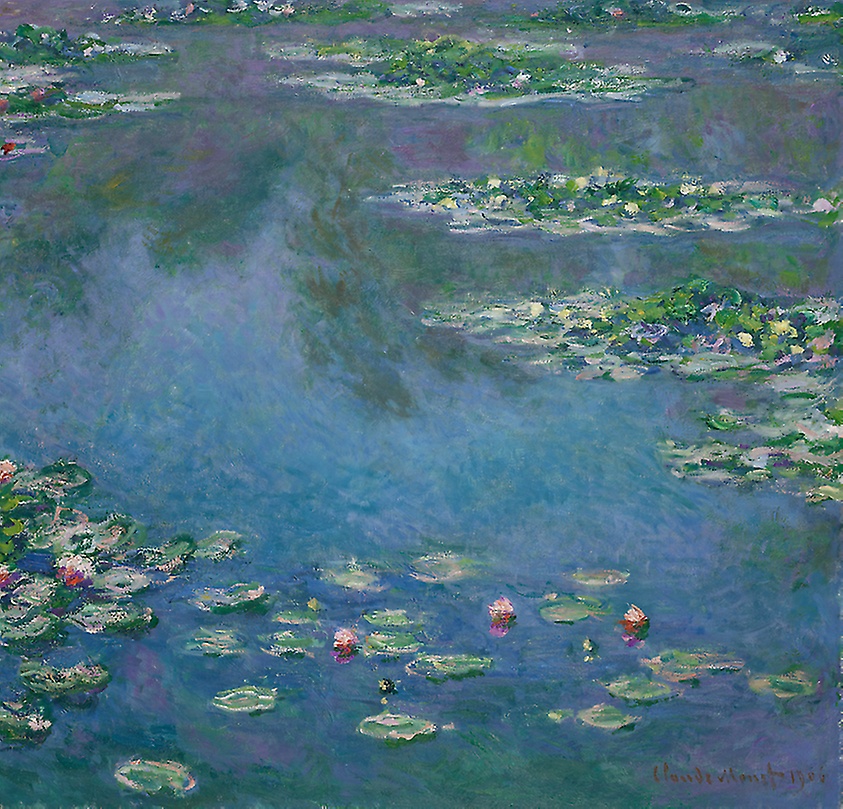

It must be a rare privilege of mine to have been able to sit and listen as an organist secretly practised hymns in an empty church. My eavesdropping presents an imbalance of power, in a sense. A person in the company of others acts according to a social performance, conscious or otherwise. A person who believes he is alone acts only in the sight of his private God; and when he is seen without his knowledge he performs a social role without knowing so, even unconsciously. A friend of mine thought to pose this question to herself: What is a positive image of a submissive power dynamic? One answer, that she suggested, is “trust”. Another might be: the freedom from social judgement. The freedom of the surface of a pond to go on in its private operation of supporting the water lilies, and scattering sunlight through its translucent body, without the crippling knowledge that its likeness is being captured by Claude Monet. The affirmative power of submission is in the freedom from the compulsion toward self mastery.

The whimsy of the church scene is obvious, but less obvious is the unique beauty of the music itself. By any usual standard of instrumental skill, the organist wasn’t very good. He didn’t make too many mistakes, but the struggle to hit the right keys in the right order made his timing unsteady and hesitant. Perhaps taken at face value, any one of these small performances would have been disappointing. Taken within the continuity of his wider practise session though, they quickly took on a magical quality. As he played, and small mistakes would pile up, I began to feel, with a palpable rise in tension that corresponded to his rising rhythmic sloppiness, that a wrong note was coming. Whenever the bum note appeared, playing would stop immediately. These silences were electrifying and tense. Sometimes they would be quickly snuffed out by the resuming of playing, sometimes they would linger for as long as any silence has ever hung in still air. The internal musical rhythmic framework of the pieces, even if unsteady, was that of regular beats and measures. The relationships between the lengths of notes and rests tended to be in the halves and quarters of minims, crotchets and quavers. Within the wider session, the faltering regularity of the internal rhythms of the pieces came up against the unbounded time of life, the time of freely drifting intervals, of silences that last lifetimes and instants that are gone sooner than perception can catch them. The regularity of music alongside the free time of frustrated silence.

In his 1977 book The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the Nineteenth Century Wolfgang Schivelbusch describes the ways in which the radical newness of the train allowed for—and necessitated—new ways of conceiving of space and time. Or indeed—and this is the same thing phrased another way— new ways for a consciousness to reflect on its own motion through a medium of direction and orientation. Schivelbusch writes that “the train was experienced as a projectile, and traveling on it, as being shot through the landscape—thus losing control of one’s senses.” To the nineteenth century passenger, this motion was alien, without grounding in the historical memory of the previous hundreds of thousands of years of our species, and so the perception of this motion through space could not take its usual form—travelers had to acclimatise to the extremity of it. A panoramic perception developed—foreground having been rendered blurry and unaccountable by speed, the only possible perception was a broad view of distances and landscapes framed by flux. The panoramic view stresses separations and individual subjectivity—incommensurable divisions between the tangible reality of the countryside and the ballistic blur that move the subject through that landscape, and incommensurable divisions between a subject and its field. “Panoramic perception, in contrast to traditional perception, no longer belonged to the same space as the perceived objects: the traveler saw the objects, landscapes, etc. through the apparatus which moved him through the world.”

I thought about John Cage’s Cheap Imitation on the walk home. That piece is based on the rhythms of Erik Satie’s Socrate, with the notes changed according to instruction from the I Ching. Another of Cage’s pieces, Some of “The Harmony of Maine”, takes the notes of a nineteenth century hymn and modifies the rhythm, extending the duration of some notes and removing others entirely according to similar instruction. Some of “The Harmony of Maine” is a work for the organ, an instrument from which sound emanates from a series of different pipes at different and distinct locations separated in space. The recorded version for Klang der Wandlungen, a collection of recordings of Cage’s late works released in 2017 by Edition RZ, is played by the wonderful Jakob Ullmann. It lasts for almost an hour, during which the melodies of the original hymn are sometimes contorted by the chance operations into immense drones, too massive to be perceived as part of the same melodic structure of the faster sections. Cage’s music often takes the form of an affirmative picture of limitation, an affirmative picture of a freedom from traditional harmony or the linear perception of time. For Cage, silence is not a negation or absence of sound but another kind of sound: a positive force that can act and be acted on. His move towards including silence in sound was a move towards recognising the continuity of sound, and therefore music. It is towards the recognition that to distinguish between silence and music is to make a normative judgment, an ideological exclusion. Music is continuous, it is we who turn away.

Since coming across that magical scene outside the church, I started going to the site at the same regular time to try and find it again. As of this writing, I never have. My happiness at the discovery of such a beautiful old building, and such a secret performance, was tempered by my mild annoyance that I was using its discovery as a way of retroactively justifying my arbitrary walk, which doesn’t need justification. Attentive readers might have noticed that the sentence “the affirmative power of submission is in the freedom from the compulsion toward self mastery” is an assertion that a negative freedom, a freedom from, is somehow an affirmative power. These contradictions are normal.